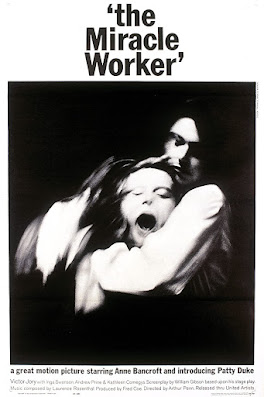

Plot intro

Alabama, 1887. The Keller family don’t know what to do with their seven-year-old deaf-blind daughter Helen (Patty Duke). They have very few ways to communicate with her and she wanders the house and grounds like a lost animal. Horrified by the idea that she may end up in an asylum, they hire a young woman named Anne Sullivan (Anne Bancroft), a partially-sighted tutor who is determined to show Helen how to connect with the world.

Our journey through the Best Actress Oscar has, so far, been a little disappointing throughout the 1950s. While we’ve seen strong performances and some fun and interesting pieces, nothing has impressed or wowed us. Not since '40s movies such as Gaslight, The Farmer’s Daughter and The Heiress have I felt motivated to re-watch anything. But along comes The Miracle Worker to obliterate this string of mediocrity. It is one of the most moving, fascinating and emotional films that we’ve blogged about; a hidden, somewhat-forgotten gem in Academy Awards history.

It wasn’t at all what I expected. When discovering it was about the relationship between Helen Keller and the tutor who taught her to communicate, I braced myself for a twee, saccharine tale with earnest speeches about education and disabilities. But this film has not one sentimental bone in its body. As the film opens, we quickly discover that seven-year-old Helen Keller is like a feral animal. She knocks things over and breaks things without thought of consequence, takes food and drink from others’ plates, and lashes out at anyone who tries to stop or steady her. Her parents have essentially given up. They adore their daughter, but are convinced she cannot learn otherwise, so they don’t teach her to be a part of society. As a result, like all humans who have been allowed too much control (regardless of age and ability), Helen resorts to physical violence to get what she wants- and often wins.

When Anne Sullivan arrives, Helen doesn’t undergo a sudden, miraculous (despite the title) transformation into an angelic Mary Sue. Goodness me, no. The two of them have lengthy brawls and conflicts that would make a cage fighter wince. Anne is determined to show Helen that she can only have what she wants if she asks for it, whether that be by hand gesture, touch or whatever sounds she can make. But the spoiled, ferocious and terrified Helen has other ideas. A breakfast scene in which Anne forces Helen to ask for food, sit at her own place and eat with a spoon involves hitting, kicking, dragging across the floor, throwing objects, and throwing water. It lasts nearly 10 minutes. It’s a gruelling, vicious process in which you are cheering Anne to keep going and crying out for Helen to heed Anne’s lesson. It’s a realistic reminder that teaching children, particularly SEND (Special Educational Needs and Disabilities) children, is rarely a beautiful, serene process, but more often an uncomfortable and confrontational one. As a primary school teacher, it was quite triggering.

The energy that both Bancroft and Duke required for these scenes (and there are several) is unparalleled. You can see the sweat and exhaustion in them and apparently they had padding under their costumes to avoid injury although God knows how they protected their faces and hands. Both of them won Oscars for these roles and both deserved it. Duke especially (who, incidentally, is the mother of Sean Astin, Sam from Lord of the Rings) moves with the scared, erratic clumsiness of someone who is genuinely deaf-blind. It is remarkable that she defeated Angela Lansbury and Thelma Ritter to the award without a single line of dialogue. Bancroft also delivers one of the greatest Best Actress performances ever. Her speech to Helen’s parents about her experiences in an asylum, a place where society would put away any woman who is inconvenient to society (the elderly, the disabled, the poor and, she infers, the homosexual) is chilling. Her tenacity and ruthless kindness towards Helen bursts from the screen. She defeated hot favourite Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? and as much as I love Davis in that film, Bancroft is a more deserving winner. The award was famously accepted by Davis’ co-star and arch-nemesis Joan Crawford, much to Davis’ fury (or so the legends say).

Another aspect of the film I appreciated was the depiction of Helen’s parents and brother. It would have been so easy to show them as cruel, distant, bigoted. But the writing is very fair to them. They are understandably stressed and terrified about Helen’s future. Without any education regarding Helen’s potential, they come to the very natural (though incorrect) conclusion that Helen will never really do anything. Anne Sullivan was just 20 years old when they hired her with no tutoring experience other than her own partial blindness. The film reiterates that their hiring of her is a desperate and last resort, and one they very nearly give up on. I felt myself internally screaming at them to keep Anne in their employ, to believe her, and to keep going.

The Miracle Worker is an emotional film, one in which you feel the stress, anger and exhilaration of every character so that Helen’s eventual communication at the climax is a relief like no other. While Helen Keller (who was still alive at the time of the film’s release and met Patty Duke) and others had campaigned for disability rights and education in the USA and internationally, it was not until after WWII that real progress and research was made into understanding SEND and finding ways to educate children who, in the past, would have been locked away from society. The '50s and '60s was a time of reassessment and rebuilding post-war and The Miracle Worker, with its powerful and energetic messages of integrating, educating and finding the true potential in children with disabilities, is an important work of art in this period.

Later in the film, Anne finally manages to get Helen to follow and obey household routines, most importantly sitting at the table and eating food from her own plate like the rest of the family. As the family gathers for their first meal after this change, director Arthur Penn frames the dining room with lovely symmetry, suggesting serenity and peace at last. But quietly, out of the corner of your eye, you notice that Helen is refusing to wear her napkin (a rule of the household). Slowly you realise that, despite her disabilities, Helen, just like any other child, will try to push boundaries and assert control. Carnage, of course, ensues.

None at all- I was captivated from start to finish. I was cheering on every character to succeed as if I was watching a sports event in which I supported both sides.

Was…was this film made yesterday? I only ask because it feels so fresh that I wouldn’t be surprised to find out we accidentally watched a remake that took modern parenting and disability challenges into account. Also, after the last three films - Signoret in Room at the Top (unfaithful, bitter, dies horribly); Taylor in BUtterfield 8 (promiscuous, flippant, dies horribly) and Loren in Two Women (wild, promiscuous, raped and broken) - to see this story of resilient women winning at life is like cool water flowing over my skin (yes, that’s a reference).

Not since we watched Rocky in our Best Films project has a film been such a surprise. I settled down to watch two hours of awkward, ableist film-making and instead found myself utterly glued to the screen for two hours. It ended and I was annoyed there wasn’t another hour.

Paul’s gone into detail on why this film is so outstanding but I have to echo him and talk about the breakfast scene. Bancroft is exceptional in showing how Anne Sullivan is outraged at the Kellers’ refusal to try and teach Helen how to behave. The ensuing lengthy scene in which Helen and Anne battle it out is ferocious, gritty - and realistic. I think it’s hugely telling that they played these parts on Broadway because they are utterly inside these roles. Patty Duke, playing deaf-blind despite being neither (I know it’s problematic but this was 1962) is so convincing in her movement. There is a desperation and loneliness that drips through her whole performance and the fear - yet fascination - with Anne who refuses to act as others do is phenomenal.

I do want to shout out to the actors playing the family. Victor Jory and Inga Swenson do sterling work as the adoring, helpless parents who don’t know how to treat their daughter and Andrew Prine found real depths in the half-brother who is torn between a nihilistic abandonment of his sister and holding his parents to account for their less-than-amazing approach to parenting.

Let’s be frank. This is Bancroft’s film. Yes, there’s the amazing monologue where she tells them of her horrifying start in life and when Mrs Keller starts to look pitying, she snaps and says ‘No! It made me strong!’ But it’s everything else she does here that nabs it for me. The amused way she looks at Helen when she realises how clever the deaf-blind girl is. The passion with which she refuses to ever give up. ‘Give them back their dog and their child, both housebroken’ she snarls when the parents, satisfied that Helen has learnt some table manners, insist she come back to them.

She wants more for Helen - she wants her to connect with the world and be able to be part of it. It’s not about being obedient, it’s about not being alone and isolated. The famous water pump scene is deeply moving in how hard-earned it has been, not just for Anne and Helen, but also for us as viewers. Nothing has come easy in this film - and it’s telling that it ends before Helen learns how to speak a single word (which the real Keller did learn to). This is the hardest bit of her journey, but there’s still a long way to go.

Director Arthur Penn holds true and steady throughout. The scene Paul mentions with the napkin being dropped is so brilliantly shot that it would receive laudits if it were released tomorrow. The happy family, reunited, and certain that everything is good again are back and celebrating - and a simple napkin being dropped becomes chillingly ominous. I didn’t love the note of Anne telling Helen she loves her at the end because it struck a slightly schmaltzy note in a gritty, no-holds-barred film - but I’m being picky.

Bancroft is a revelation. The fury when she upbraids the stern father for his collusive behaviour, the softness with which she approaches the wild Helen - and her astonishing muscularity as she hauls Helen from chair to table. It’s unlike any other performance we’ve seen so far.

The aforementioned hint of schmaltz at the end - and an oddly abrupt ending left me a tiny bit cold. No title cards? No quick wrapping up or summary of Helen’s life afterwards? But these are quibbles. An astonishing piece of work.

Mark

10/10

No comments:

Post a Comment